Two math conversations with GPT-4o

I had two math conversations with GPT-4o, and I want to share them with you. I will show both of them.

For who doesn’t know, GPT-4o is the new OpenAI’s model that is able to process text, video and audio at the same time. We’ll see how it compares to Claude 3.5 Sonnet.

Both conversations happened on the 21st of July 2024.

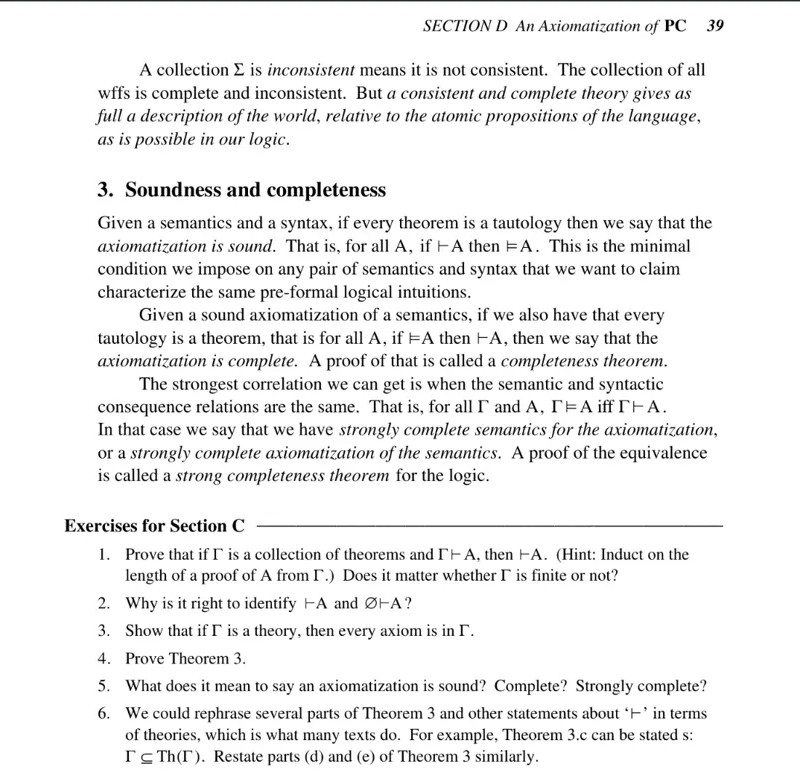

The shown images belong to the book Richard L. Epstein, Leslaw W. Szczerba - Classical Mathematical Logic - The Semantic Foundations of Logic - Princeton University Press (2006).

First conversation

User: Can you explain chapter 3?

Certainly! The chapter you’re referring to discusses the concepts of soundness and completeness in the context of formal logic. Let’s break down the content:

3. Soundness and Completeness

Soundness:

- An axiomatization (a set of axioms and inference rules) is sound if every theorem it produces is a tautology (a statement that is true in all interpretations).

- In formal terms, this means that for all statements \( A \), if \( \vdash A \) (A is a theorem), then \( \models A \) (A is a tautology).

- Soundness ensures that our axiomatization does not produce any false theorems.

Completeness:

- An axiomatization is complete if every tautology is a theorem.

- This means that for all statements \( A \), if \( \models A \), then \( \vdash A \).

- Completeness ensures that our axiomatization is capable of proving all true statements (tautologies).

Strong Completeness:

- The strongest correlation is when the semantic consequence relation \( \models \) and the syntactic consequence relation \( \vdash \) are the same.

- This is formally expressed as: for all sets of statements \( \Gamma \) and statements \( A \), \( \Gamma \models A \) if and only if \( \Gamma \vdash A \).

- When this holds, we say we have strongly complete semantics for the axiomatization, or a strongly complete axiomatization of the semantics.

- A proof of this equivalence is called a strong completeness theorem.

Exercises for Section C

-

Prove that if \( \Gamma \) is a collection of theorems and \( \Gamma \vdash A \), then \( \vdash A \):

- This involves proving that if a set of theorems \( \Gamma \) syntactically entails \( A \), then \( A \) itself must be a theorem.

- Hint: Use induction on the length of a proof of \( A \) from \( \Gamma \).

- Consider whether \( \Gamma \) is finite or not, as it might affect the induction process.

-

Why is it right to identify \( \vdash A \) and \( \emptyset \vdash A \)?

- This is asking for a justification that proving \( A \) with no assumptions (from an empty set of axioms) is the same as \( A \) being a theorem.

-

Show that if \( \Gamma \) is a theory, then every axiom is in \( \Gamma \):

- A theory \( \Gamma \) is a set of statements closed under logical consequence, meaning if \( A \) is an axiom, then \( A \in \Gamma \).

-

Prove Theorem 3:

- Theorem 3 is likely related to the definitions and statements provided above regarding soundness and completeness. The proof would typically involve formal logical reasoning and possibly reference earlier results or lemmas.

-

What does it mean to say an axiomatization is sound? Complete? Strongly complete?

- Define these terms clearly as explained above.

-

Rephrase several parts of Theorem 3 and other statements about ‘\( \vdash \)’ in terms of theories:

- For example, Theorem 3.c can be restated as \( \Gamma \subseteq \text{Th}(\Gamma) \), where \( \text{Th}(\Gamma) \) is the set of all theorems that can be derived from \( \Gamma \).

- Restate parts (d) and (e) similarly.

Summary

- Soundness ensures no false theorems are produced: \( \vdash A \implies \models A \).

- Completeness ensures all true statements can be proved: \( \models A \implies \vdash A \).

- Strong Completeness is when the semantic and syntactic consequence relations are equivalent.

Understanding these concepts is fundamental in formal logic as they establish the reliability and power of an axiomatization in capturing all truths within a logical system.

User: Can you solve the first three exercises of the chapter?

Sure, let’s work through the first three exercises:

Exercise 1

Prove that if \( \Gamma \) is a collection of theorems and \( \Gamma \vdash A \), then \( \vdash A \):

Hint: Induct on the length of a proof of \( A \) from \( \Gamma \). Does it matter whether \( \Gamma \) is finite or not?

Solution:

Given:

- \( \Gamma \) is a collection of theorems, meaning every \( \gamma \in \Gamma \) is a theorem \( \vdash \gamma \).

- \( \Gamma \vdash A \), meaning \( A \) can be derived from the set of theorems \( \Gamma \).

We need to show \( \vdash A \), meaning \( A \) is a theorem on its own.

Proof by Induction on the length of the proof of \( A \) from \( \Gamma \):

-

Base Case: Length of proof is 1.

- If \( A \) can be derived in one step from \( \Gamma \), then \( A \in \Gamma \). Personal note: little GPT-4o imprecision: \( A \) could be an axiom, therefore not necessarily in \( \Gamma \).

- Since \( \Gamma \) is a collection of theorems, \( \vdash A \).

-

Inductive Step:

- Assume for proofs of length \( n \), if \( \Gamma \vdash A \), then \( \vdash A \).

- Consider a proof of \( A \) from \( \Gamma \) of length \( n+1 \). This means there exists a formula \( B \) such that:

- \( \Gamma \vdash B \) (proof of length \( n \))

- \( B \rightarrow A \) is a theorem (since inference rules or axioms are used to derive \( A \) from \( B \))

- By the induction hypothesis, \( \vdash B \) because \( \Gamma \vdash B \).

- Since \( B \rightarrow A \) is a theorem, \( \vdash B \rightarrow A \).

- From \( \vdash B \) and \( \vdash B \rightarrow A \), by modus ponens, \( \vdash A \).

Claude Sonnet says:

Inductive step: Consider a proof of length k+1. The last step in this proof can be: a) An axiom: Then ⊢ A directly. b) A member of Γ: Then A is a theorem, so ⊢ A. c) Derived by a rule of inference from previous steps: These previous steps are either axioms, members of Γ, or derived from them in k or fewer steps. By the inductive hypothesis, each of these previous steps B is such that ⊢ B. Since rules of inference preserve theoremhood, we can conclude ⊢ A.

Personal note: I prefer more Claude's explanation, it's more complete since it consider all the other cases as well. But to that answer I would add GPT-4o's explanation of the inductive step, it's very clear.

Therefore, by induction, if \( \Gamma \) is a collection of theorems and \( \Gamma \vdash A \), then \( \vdash A \), regardless of whether \( \Gamma \) is finite or not.

Exercise 2

Why is it right to identify \( \vdash A \) and \( \emptyset \vdash A \)?

Solution:

In formal logic, \( \vdash A \) means that \( A \) is a theorem, which can be proved without any assumptions. This implies that \( A \) can be derived from the empty set of assumptions.

- \( \vdash A \) indicates that \( A \) is derivable from the axioms alone, with no additional premises.

- \( \emptyset \vdash A \) explicitly states that \( A \) is derivable when there are no premises (the empty set of premises).

Since both statements indicate that \( A \) is derivable purely based on the axioms and inference rules (and no other assumptions), they are equivalent. Therefore, it is right to identify \( \vdash A \) with \( \emptyset \vdash A \).

Exercise 3

Show that if \( \Gamma \) is a theory, then every axiom is in \( \Gamma \):

Solution:

A theory \( \Gamma \) is defined as a set of formulas that is closed under logical consequence. This means if a formula \( A \) is a logical consequence of \( \Gamma \), then \( A \) is in \( \Gamma \).

- Axioms are formulas that are considered true in every interpretation and can be derived without any premises.

- For any axiom \( A \), \( \vdash A \).

- Since \( \Gamma \) is a theory, it is closed under logical consequence. This means that if \( \vdash A \), then \( A \in \Gamma \). Personal note: here GPT is not really explaining why, or at least well enough IMO.

Personal note: Claude Sonnet instead says:

Exercise 3: Show that if Γ is a theory, then every axiom is in Γ.

Proof:

- Let A be any axiom of the logical system.

- By definition, ⊢ A (axioms are theorems).

- If ⊢ A, then Γ ⊢ A for any set Γ (including theories), because deriving A doesn’t depend on Γ.

- Since Γ is a theory, it’s closed under deduction. This means if Γ ⊢ A, then A ∈ Γ.

- Therefore, A ∈ Γ.

Since A was an arbitrary axiom, we can conclude that all axioms are in Γ.

Therefore, if \( \Gamma \) is a theory, then every axiom \( A \) must be in \( \Gamma \).

There was no need to ask these questions since the model already answered them:

User: I’m very lost. Can you solve the first one?

User: Can you solve exercise 2?

User: I’m providing you the definition of theory as well in the context of mathematical logic. Now, can you help me understand this and also solve exercise 6?

Certainly! Let’s first understand the additional information provided and then solve exercise 6.

Understanding the Definition and Theorem 3

Theorem 3: Properties of Syntactic Consequence Relations

a. Reflexivity: \( A \vdash A \)

- Every formula \( A \) syntactically entails itself.

b. Weakening (Monotonicity): If \( \Gamma \vdash A \), then \( \Gamma \cup \Delta \vdash A \)

- If a set of formulas \( \Gamma \) entails \( A \), then adding more formulas to \( \Gamma \) does not change the fact that \( A \) is entailed.

c. Axiom: If \( A \in \Gamma \), then \( \Gamma \vdash A \)

- Any formula in \( \Gamma \) is entailed by \( \Gamma \).

d. Monotonicity: If \( \Gamma \vdash A \) and \( \Gamma \subseteq \Delta \), then \( \Delta \vdash A \)

- If \( \Gamma \) entails \( A \), and \( \Gamma \) is a subset of \( \Delta \), then \( \Delta \) also entails \( A \).

e. Transitivity: If \( \Gamma \vdash A \) and \( A \vdash B \), then \( \Gamma \vdash B \)

- If \( \Gamma \) entails \( A \) and \( A \) entails \( B \), then \( \Gamma \) entails \( B \).

f. Cut Rule: If \( \Gamma \vdash A \) and \( \Gamma, A \vdash B \), then \( \Gamma \vdash B \)

- If \( \Gamma \) entails \( A \), and \( \Gamma \) together with \( A \) entails \( B \), then \( \Gamma \) entails \( B \).

g. Compactness: If \( \Gamma \cup {A_1, \ldots, A_n} \vdash B \) and for each \( i = 1, \ldots, n \), \( \Gamma \vdash A_i \), then \( \Gamma \vdash B \)

- If \( \Gamma \) together with a finite set of formulas entails \( B \), and each of those formulas is entailed by \( \Gamma \), then \( \Gamma \) entails \( B \).

h. Compactness: \( \Gamma \vdash A \) iff there is some finite collection \( \Delta \subseteq \Gamma \) such that \( \Delta \vdash A \)

- If \( \Gamma \) entails \( A \), then there is a finite subset of \( \Gamma \) that also entails \( A \).

Theories:

- \( \Sigma \) is a theory if it is closed under syntactic deduction: if \( \Sigma \vdash A \), then \( A \in \Sigma \).

- The collection of all syntactic consequences of \( \Sigma \) is the theory of \( \Sigma \), written as \( \text{Th}(\Sigma) = { A: \Sigma \vdash A } \).

- Thus, \( \Sigma \) is a theory iff \( \text{Th}(\Sigma) = \Sigma \).

Consistency and Completeness:

- \( \Gamma \) is consistent if for every \( A \), \( \Gamma \not\vdash A \land \neg A \).

- \( \Gamma \) is complete iff for every \( A \), either \( \Gamma \vdash A \) or \( \Gamma \vdash \neg A \).

Solving Exercise 6

Exercise 6: We could rephrase several parts of Theorem 3 and other statements about ‘\(\vdash\)’ in terms of theories: For example, Theorem 3.c can be stated as: \( \Gamma \subseteq \text{Th}(\Gamma) \). Restate parts (d) and (e) of Theorem 3 similarly.

Solution:

Theorem 3.d (Monotonicity): If \( \Gamma \vdash A \) and \( \Gamma \subseteq \Delta \), then \( \Delta \vdash A \).

- In terms of theories: If \( \Gamma \) is a subset of \( \Delta \), and \( A \) is a theorem of \( \Gamma \), then \( A \) must also be a theorem of \( \Delta \).

- This can be restated as: \( \Gamma \subseteq \Delta \implies \text{Th}(\Gamma) \subseteq \text{Th}(\Delta) \).

Theorem 3.e (Transitivity): If \( \Gamma \vdash A \) and \( A \vdash B \), then \( \Gamma \vdash B \).

- In terms of theories: If \( A \) is a theorem of \( \Gamma \), and \( B \) is a theorem of the theory generated by \( A \), then \( B \) must be a theorem of \( \Gamma \).

- This can be restated as: If \( A \in \text{Th}(\Gamma) \) and \( B \in \text{Th}({A}) \), then \( B \in \text{Th}(\Gamma) \).

To summarize:

- Theorem 3.c: \( \Gamma \subseteq \text{Th}(\Gamma) \).

- Theorem 3.d: \( \Gamma \subseteq \Delta \implies \text{Th}(\Gamma) \subseteq \text{Th}(\Delta) \).

- Theorem 3.e: If \( A \in \text{Th}(\Gamma) \) and \( B \in \text{Th}({A}) \), then \( B \in \text{Th}(\Gamma) \).

User: Can you explain why Th(Σ) = Σ and solve exercise 3?

Explanation of \( \text{Th}(\Sigma) = \Sigma \)

A theory \( \Sigma \) is defined as a set of formulas that is closed under syntactic deduction. This means if a formula \( A \) can be derived from \( \Sigma \), then \( A \) is already in \( \Sigma \). Formally, this is written as \( \Sigma = \text{Th}(\Sigma) \), where \( \text{Th}(\Sigma) \) is the set of all formulas that can be derived from \( \Sigma \).

- \(\text{Th}(\Sigma)\) is the set of all syntactic consequences of \( \Sigma \). That is, \( \text{Th}(\Sigma) = \{A : \Sigma \vdash A\} \).

- \(\Sigma\) is a theory if every formula that can be derived from \( \Sigma \) is already in \( \Sigma \). This implies that \( \Sigma \) includes all its syntactic consequences, i.e., \( \Sigma \vdash A \implies A \in \Sigma \).

So, if \( \Sigma \) is a theory, then \(\Sigma\) contains exactly those formulas that can be derived from it, hence \( \text{Th}(\Sigma) = \Sigma \).

Exercise 3: Show that if \(\Gamma\) is a theory, then every axiom is in \(\Gamma\).

Given that \(\Gamma\) is a theory, we need to show that every axiom is in \(\Gamma\).

Solution:

Definition of a Theory:

- A set of formulas \(\Gamma\) is a theory if it is closed under syntactic deduction. This means if \( \Gamma \vdash A \), then \( A \in \Gamma \).

Axioms:

- Axioms are formulas that are assumed to be true without proof. In many logical systems, axioms are taken as starting points for deductions.

We need to show that if \( \Gamma \) is a theory, then all axioms \( A \) are in \(\Gamma\).

Proof:

-

Axioms are Theorems:

- By definition, axioms are formulas that are true in every interpretation. In syntactic terms, this means \( \vdash A \) for every axiom \( A \).

-

Closure under Deduction:

- Since \(\Gamma\) is a theory, it is closed under syntactic deduction. This means if \( \vdash A \), then \( A \in \Gamma \).

-

Axioms in \(\Gamma\):

- Since \(\vdash A\) holds for every axiom \( A \), and \(\Gamma\) is a theory (which means it contains all formulas derivable from it), every axiom \( A \) must be in \(\Gamma\).

Personal note: It answers in the same way as before.

Hence, if \(\Gamma\) is a theory, then every axiom \( A \) is in \(\Gamma\). This completes the proof.

Second conversation

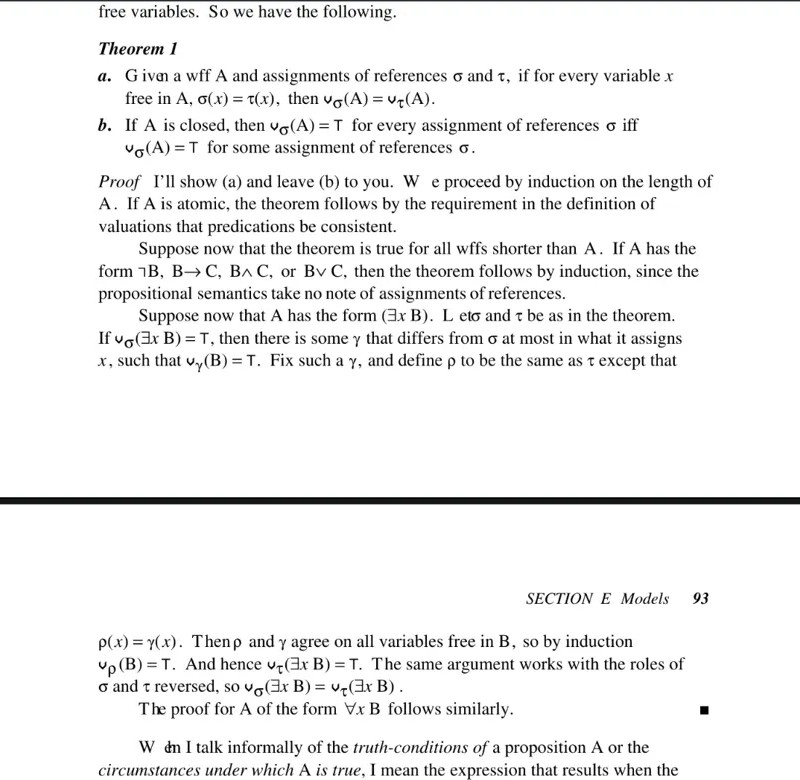

User: Can you explain the last part of the part (a) of the proof? I don’t get the application of the induction

Sure, let’s take a closer look at the last part of the proof for part (a) of the theorem. I will transcribe and analyze the relevant section for clarity.

Transcription of the Last Part of the Proof (a)

Here’s the transcription of the relevant portion:

Suppose now that A has the form (∃x B). Let σ and τ be as in the theorem. If υσ(∃x B) = T, then there is some γ that differs from σ at most in what it assigns to x, such that υγ(B) = T. Fix such a γ, and define ρ to be the same as τ except that ρ(x) = γ(x). Then ρ and γ agree on all variables free in B, so by induction υρ(B) = T. And hence υτ(∃x B) = T. The same argument works with the roles of σ and τ reversed, so υσ(∃x B) = υτ(∃x B).

Explanation

Let’s break this down step by step to understand the induction application.

-

Initial Assumption for the Induction: We assume that the theorem holds for all well-formed formulas (wffs) shorter than \( A \). This means if we have proven the statement for simpler or shorter formulas, we can use that to prove it for more complex ones.

-

Considering \( A \) of the Form \( \exists x B \): Here, \( A \) is considered to be a formula of the form \( \exists x B \), where \( B \) is a subformula.

-

Valuation Under Assignment \( \sigma \):

- We start by assuming \( υσ(∃x B) = T \). This means under the assignment \( \sigma \), the formula \( \exists x B \) is true.

- By the semantics of existential quantification, this implies that there exists some assignment \( \gamma \) which differs from \( \sigma \) at most in what it assigns to \( x \), such that \( υγ(B) = T \).

-

Constructing \( ρ \):

- We fix such a \( \gamma \) and define a new assignment \( ρ \) to be the same as \( τ \) except that \( ρ(x) = γ(x) \). Essentially, \( ρ \) assigns the same values as \( τ \) to all variables except \( x \), which is assigned the same value as in \( γ \).

-

Induction Hypothesis Application:

- Since \( ρ \) and \( γ \) agree on all variables free in \( B \) (because \( ρ \) only differs from \( τ \) in the assignment to \( x \), and \( x \) is not free in \( B \) after \( ∃x \)), by the induction hypothesis, we can say \( υρ(B) = T \).

-

Conclusion for \( υτ(∃x B) \):

- Given \( υρ(B) = T \) and \( ρ \) is essentially \( τ \) with the required assignment for \( x \), it follows that \( υτ(∃x B) = T \).

-

Symmetry Argument:

- The argument works similarly if we reverse the roles of \( σ \) and \( τ \). This shows that the valuation is independent of the specific assignments, provided they agree on the free variables.

Therefore, by induction, the statement holds for the formula \( \exists x B \).

Summary

In essence, the induction step is used to handle formulas of the form \( \exists x B \). By assuming the theorem holds for all subformulas \( B \) (the induction hypothesis), we can show it also holds for \( \exists x B \) by carefully constructing new assignments and showing the valuations agree under these assignments. This completes the induction step and thus the proof for part (a).

User: Give a formal definition of the following concepts: wwf, assignment of references σ, valuation υ

Certainly! Here are formal definitions of the concepts mentioned:

Well-formed Formula (wff)

A well-formed formula (wff) in the context of first-order logic is a string of symbols that is constructed according to the syntactical rules of the logical language. It is a meaningful expression that can be true or false under some interpretation. Formally, the set of wffs is defined inductively as follows:

-

Atomic Formulas:

- If \( P \) is an \( n \)-ary predicate symbol and \( t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_n \) are terms, then \( P(t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_n) \) is a wff.

- If \( t_1 \) and \( t_2 \) are terms, then \( t_1 = t_2 \) is a wff.

-

Logical Connectives:

- If \( A \) and \( B \) are wffs, then \( \neg A \), \( (A \wedge B) \), \( (A \vee B) \), \( (A \rightarrow B) \), and \( (A \leftrightarrow B) \) are wffs.

-

Quantifiers:

- If \( A \) is a wff and \( x \) is a variable, then \( \forall x A \) and \( \exists x A \) are wffs.

Assignment of References (\( \sigma \))

An assignment of references \( \sigma \) in the context of first-order logic is a function that maps each variable to an element of the domain of discourse (also called the universe of discourse). Formally:

- Let \( D \) be the domain of discourse.

- An assignment \( \sigma \) is a function \( \sigma: \text{Var} \rightarrow D \), where \( \text{Var} \) is the set of all variables.

Valuation (\( υ \))

A valuation \( υ \) in first-order logic is a function that assigns truth values (true or false) to well-formed formulas under a given interpretation and an assignment of references. Formally, a valuation \( υ \) is defined as follows:

- Given a structure \( \mathcal{M} = (D, I) \), where \( D \) is the domain of discourse and \( I \) is the interpretation function that assigns meanings to the non-logical symbols (constants, function symbols, and predicate symbols), and an assignment \( \sigma \):

- \( υ_{\sigma}(t) \) evaluates terms \( t \) to elements of the domain \( D \).

- \( υ_{\sigma}(P(t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_n)) = \text{True} \) if and only if \( (υ_{\sigma}(t_1), υ_{\sigma}(t_2), \ldots, υ_{\sigma}(t_n)) \in I(P) \), where \( I(P) \) is the interpretation of the predicate symbol \( P \).

- \( υ_{\sigma}(t_1 = t_2) = \text{True} \) if and only if \( υ_{\sigma}(t_1) = υ_{\sigma}(t_2) \).

- The valuation of formulas with logical connectives and quantifiers is defined recursively:

- \( υ_{\sigma}(\neg A) = \text{True} \) if and only if \( υ_{\sigma}(A) = \text{False} \).

- \( υ_{\sigma}(A \wedge B) = \text{True} \) if and only if \( υ_{\sigma}(A) = \text{True} \) and \( υ_{\sigma}(B) = \text{True} \).

- \( υ_{\sigma}(A \vee B) = \text{True} \) if and only if \( υ_{\sigma}(A) = \text{True} \) or \( υ_{\sigma}(B) = \text{True} \).

- \( υ_{\sigma}(A \rightarrow B) = \text{True} \) if and only if \( υ_{\sigma}(A) = \text{False} \) or \( υ_{\sigma}(B) = \text{True} \).

- \( υ_{\sigma}(A \leftrightarrow B) = \text{True} \) if and only if \( υ_{\sigma}(A) = υ_{\sigma}(B) \).

- \( υ_{\sigma}(\forall x A) = \text{True} \) if and only if \( υ_{\sigma’}(A) = \text{True} \) for all assignments \( \sigma’ \) that differ from \( \sigma \) at most in the value assigned to \( x \).

- \( υ_{\sigma}(\exists x A) = \text{True} \) if and only if \( υ_{\sigma’}(A) = \text{True} \) for some assignment \( \sigma’ \) that differs from \( \sigma \) at most in the value assigned to \( x \).

Personal note: I think the model did a great job in defining these concepts, but I still prefer Claude’s answer. In fact, Claude defines the valuation function only by mentioning the negation and conjunction connectives. You can do that since \(\{ \neg, \wedge \}\) is truth-functionally complete. Furthermore, Claude’s answer uses only the universal quantifier because you can obtain the existential quantifier by negating the universal one.

Thank you for reading this post. Until the next time, bye!

Posts mentioning this post

I had two math conversations with Claude, and I want to share them with you. I will show both of them.

For who doesn’t know, Claude is a series of Large Language Models (LLMs) developed by the company Anthropic. IMO they are more powerful than OpenAI’s GPTs (but GPT-4o is catching up).

First, if you don’t know the meaning of some terms used in this post, you should check the glossary. In the glossary you can always find everything not explained in the posts.

In this post I will explain the limitations of current AI technologies, and why AGI is not here yet. I will also introduce the misuse, resources, alignment, and black box problems.